Reforms underway

With this week’s announcement of the high-level group of specialists on the EU’s cohesion policy, wheels have finally been set in motion for the next round of reforms and refinements to what is arguably one of the world’s largest development programmes.

The European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) make up over 40% of the EU’s budget, with the largest share dedicated to supporting Europe’s regions individually and to achieving higher levels of cohesion across the continent. These policies are moving towards a mid-term review in the course of 2024.

Discussions on how best to deliver such gigantic levels of funding in support of these two aims will focus, unsurprisingly, on working out what the key drivers for regional development and cohesion might be, with a view to pulling the right levers at the right time and in the right place.

Beyond the overriding matter of how much of the EU’s budget should be invested in different types of regions (a figure that has been rising steadily since the term “cohesion” entered the EU Treaties in 1987), the core of these discussions concerns the precise direction and priorities of regional growth strategies on the ground.

Theory and practice

On the back of long-standing and well-accepted economic growth theory, this means striking the correct balance between building physical infrastructure (such as motorways and energy supply), investing in human resources (such as developing education and skills) and improving the capacity for innovation on the part of individuals and firms.

These three factors have traditionally accounted for most of the EU’s cohesion investments and will, without a doubt, continue to do so. Yet as almost every practitioner will confirm, the final leg in the marathon towards sustainable regional development remains real-world implementation on the ground.

Making appropriate and well-designed strategies work in the real world remains the final success factor in the pursuit of the bigger prize, namely that of regions fulfilling their potential and growing together across the continent.

Such implementation, in turn, requires highly functioning public governance structures. Yet our understanding of the “institutions factor” when it comes to the effective deployment of public investment appears to lag behind our understanding of the factors named above.

Managing public investments

Knowledge certainly abounds on the importance of good management of public investments, and specifically its links to productivity. Applying this knowledge is highly significant, with the OECD pointing out that ESIF has funded the equivalent of 8.5% of government capital investment in the EU and up to 80% in individual member states.

Alarmingly, however, the IMF’s Public Investment Index suggests that 30% of the potential gains from public investment are lost due to inefficiencies in public investment processes. And academic research points out that government deficiencies can lead to the development of strategies that are “good looking, but without substance,” at worst benefiting clientelism rather than those who are supposed to stand to gain.

The OECD Council in 2014 adopted the Recommendation on Effective Public Investment across Levels of Government, setting out an impressive array of principles and recommendations. With reference to ESIF, the OECD points out the importance of equipping public servants with” the right tools, skills and systems to develop and manage complex projects.”

It also points to the specific requirements of “multi-level governance systems that support public investment” since EU funding in support of cohesion is carried out as a shared responsibility among national, regional, local, and European levels of government.

Put simply, while ESIF offers remarkable investment opportunities, managing these funds represents something of a challenge and requires highly effective administrative capacity to even come close to being fully realized.

The institutions factor

Yet, while this insight is neither controversial nor new, leading experts on EU cohesion efforts point to the “institutions factor” as a decided blind spot when it comes to regional development policies in Europe, with real-world implications across the continent.

The LSE’s Andrés Rodríguez-Pose, notably, argues that attempts to understand the widely diverging trajectories of regions which, on the face of things, appear quite similar may have channelled attention to factors beyond those posited by economic growth theory – namely institutions. But despite the fact that scholarly interest has grown, it is “labouring to go beyond the idea that ‘institutions matter.’”

This is a problem since, for Rodríguez-Pose, “differences in institutional quality across territories can be considered today as important as—if not more important than—variations in physical and human capital endowments and innovation capacity for the economic development of cities and regions.” Understanding the impact of these differences, in turn, could “provide the basis for a sounder and more efficient development policy at the subnational level.”

More concrete avenues of future research listed in this context concern the monopoly power of bureaucrats, new incentives in the pay structure of public administrations, the role of e-government for more efficiency and transparency, or measures aimed at increasing the education levels of civil servants. An overarching theme, clearly, is understanding “what determines the emergence of able and effective local leaders” – a nod to the aspect of informal rather than formal institutions, such as values, trust, creativity and diversity.

Capacity-building and Technical Assistance

Such thinking has certainly begun to find its way into the EU’s cohesion policy. The cohesion-related funds of ESIF have seen a portion of their budget devoted to strengthening regional governance structures by means of administrative capacity-building, that is, “developing skills, experience, technical, management and strategic capacity within an organisation.” These aims are being tackled through what is termed Technical Assistance (TA).

A study carried out by the European Policy Research Centre (EPRC) for the funding period of 2014-20 shows that at only 3.1% “TA funding accounts for a relatively small share of ESIF (ERDF, ESF, CF) across the EU 28” and is “predominantly allocated to management interventions, representing over 80% of TA funding”. It also points out that “most TA funding is allocated to Human Resources (65%), mostly in intermediate bodies and managing authorities”.

Regarding success factors for this type of administrative capacity-building, EPRC points to “well-founded, coherent and forward-looking strategies, and... good governance (based on leadership, coordination and stakeholder involvement), underpinned by a learning culture” as a prerequisite for success.

The report recommends, among other things, “support for the entire ‘ecosystem’ of ESIF management and implementation,” “the development of learning strategies for administrative capacity-building,” and “coherent management of administrative capacity building at EU level, whereby the support provided for [it] through TA should be coordinated with wider public service administrative reforms”.

Factoring-in institutions

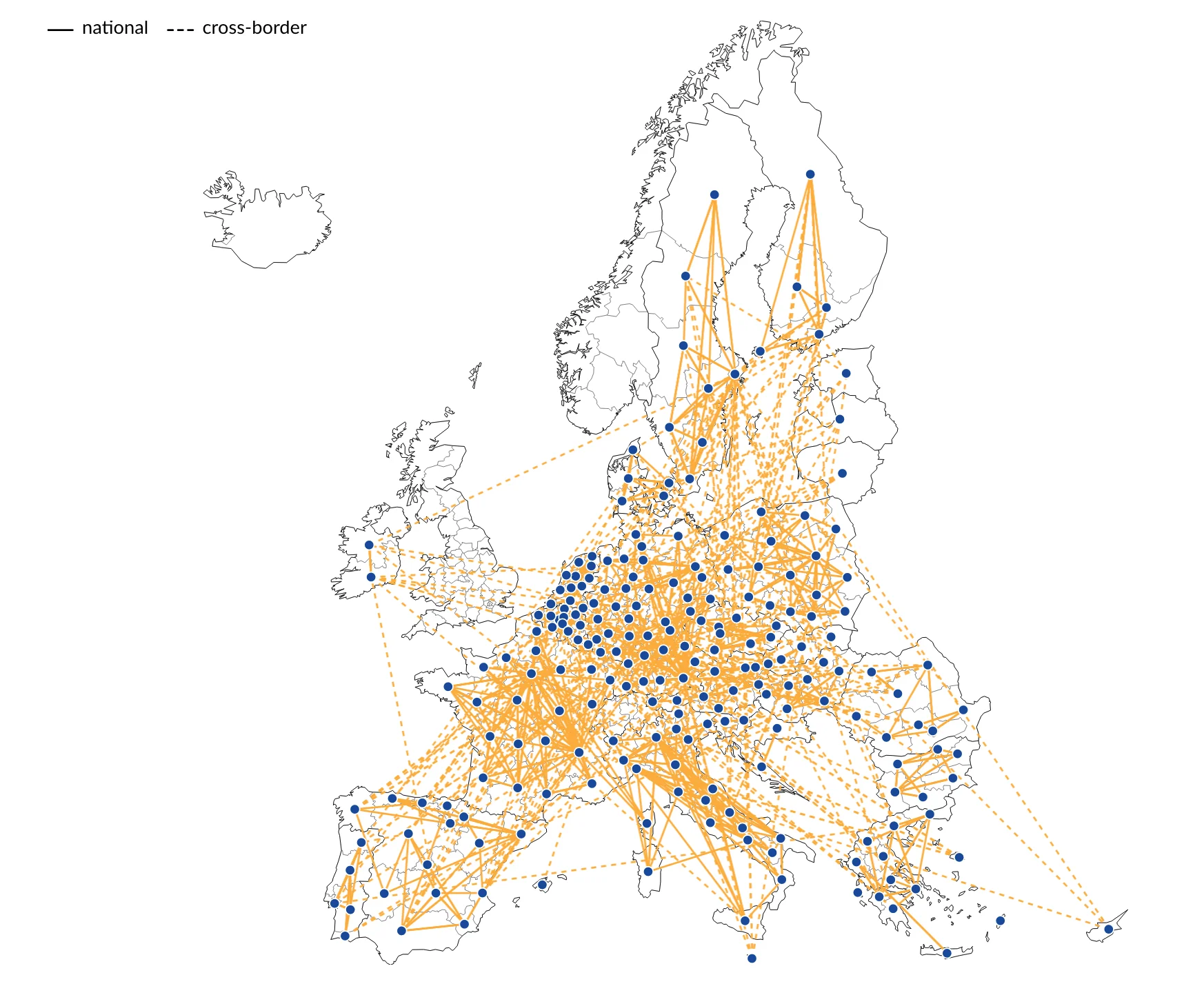

More recently, our very own analysis of the prospects of regions under the twin transition took the role of public authorities into account, using the European Quality of Government Index as an indicator of institutional quality. The index captures perceptions of, and experiences with, public sector corruption and whether public sector services are understood by citizens to be impartially allocated and of good quality.

Regions in northern and western Europe, by this measure, are institutionally the most similar, whereas institutional quality becomes more heterogeneous in eastern Europe and is most in the southern EU. It is specifically in the latter region that a strong, positive and statistically significant relationship between institutions and regional growth prospects can be seen, inviting further exploration of the precise dynamics occurring on the ground.

Institutions, then, appear to impact many key aspects of cohesion policy, including those on the high-level group of specialists’ list of priorities, such as building resilience in regions and delivering tailor-made support, enabling cooperation between regions and ensuring effective delivery, and empowering them to respond to sudden shocks and crises. Further disentangling their role will without doubt be key to realizing the EU’s grand ambition of a continent that holds together at its core.

About the author

Jake Benford is a member of Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Europe Programme, where he currently focusses on economic cohesion in the EU as well as more broadly on relations with the UK. He previously developed the foundation’s work on impact investing.

Read More on Cohesion Policy

3 Times EU Cohesion Policy Has Been Used to Address Recent Crises - Global & European Dynamics

Green, Smart and Fair: Rethinking European Cohesion in an Era of Structural Change

Upward Convergence? The History of EU Cohesion

Public Procurement as a Strategic Tool for European Economic Policy

Get Global Europe blog posts in your inbox. Sign up to receive our newsletter here.