In May 2021, Swiss leaders formally ended talks with the European Commission to create a trade framework encapsulating a raft of separate free trade agreements between Switzerland and the European Union. Since then, there has been little progress to consolidate the deals that define the EU-Swiss relationship, with only recent exploratory talks between Bern and Brussels hinting at future progress.

Our 2019 study, Estimating economic benefits of the Single Market for European countries and regions, showed that Switzerland is one of the biggest winners among countries with access to the EU single market.

Switzerland is taking a big risk with its approach to these negotiations. And for its part, the EU will want to do what it can to shore up a deal its three largest economies (those of members Germany, France, and Italy) benefit from as well, especially since they happen to be Switzerland’s immediate neighbors.

In the greater context, the trade agreements between Switzerland and the EU have long carried implications for the United Kingdom and its future relationship with the EU.

It is nearly three years since the UK officially exited the EU on January 31, 2020. Looking at Switzerland’s benefits from access to the EU single market can remind one what the UK lost, and consequently what it could gain by exploring a new free trade relationship with the EU.

EU-Swiss trade agreements then and now

In 1999, Switzerland signed a free trade agreement with the European Union later supplemented in 2004 and 2010 to ultimately comprise over 100 bilateral agreements covering everything from the free movements of goods and people (including the Schengen and Dublin programs), to public procurement, double taxation, and participation in EU scientific research and innovation programs.

Switzerland is a member of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), but narrowly rejected joining the European Economic Area (EEA) in 1992 and formerly withdrew its application to join the EU in 2016.

The renegotiation of the free trade agreements was kicked off by a 2014 Swiss referendum vote that approved restrictions on EU immigration into Switzerland, a decision incompatible with the established agreements on freedom of movement.

Despite this setback, EU-Swiss relations continued to deepen, punctuated by the 2015 agreement to automatically share banking information, a big change for the famously opaque Swiss banking sector. By 2018, a draft framework agreement was created to cement Swiss access to the single market, but Swiss leaders put negotiations on hold to reconsider.

They later returned to the EU with demands relating to the protection of Swiss wages, EU citizens’ access to Swiss welfare, and state aid. Furthermore, the final Brexit agreement between the UK and the EU played a role in Swiss leaders’ perception of their own trade framework.

The UK steered clear of a situation modeled on the EU-Ukraine association agreement in which the European Court of Justice holds sway in disagreements relating to the free trade framework. Leaders in Switzerland took notice, since their draft framework would include just that. An EU-Swiss free trade agreement that subordinates Swiss law to the ECJ is an unpopular route, and clashes with traditional Swiss independence and a need to separate economic and political integration.

Ultimately these differences could not be satisfactorily resolved, and after seven years of negotiations, Switzerland declined to sign the all-in-one deal in May 2021. Without a deal in place, the free trade agreement between the EU and Switzerland could lapse, which would result in a huge negative impact on the Swiss and EU economies.

What does access to the single market mean for Switzerland?

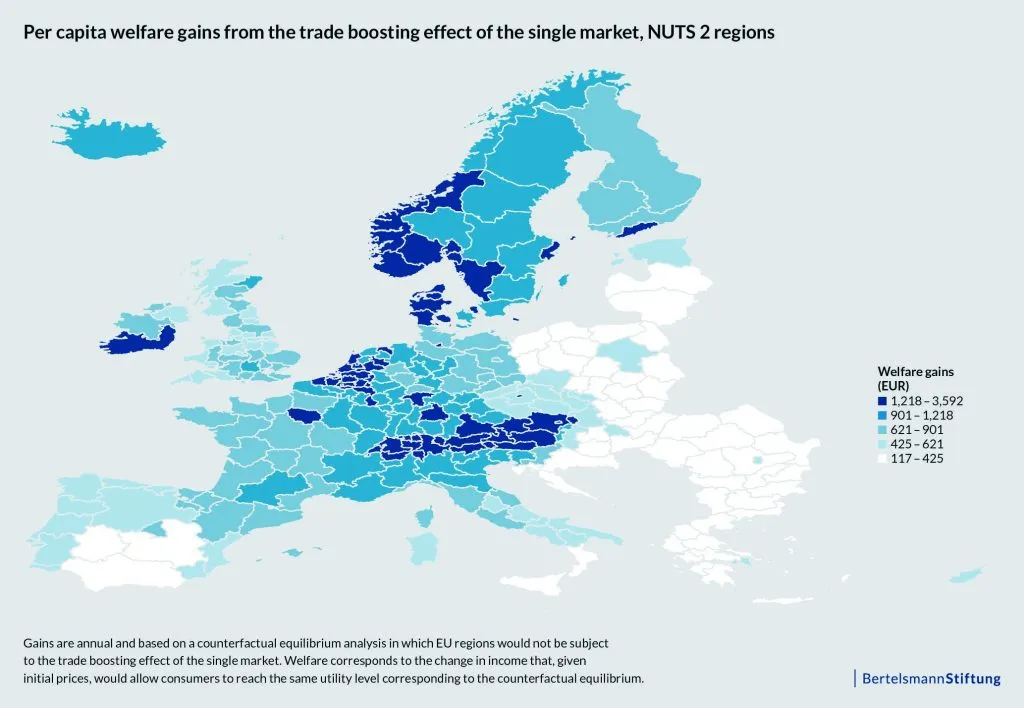

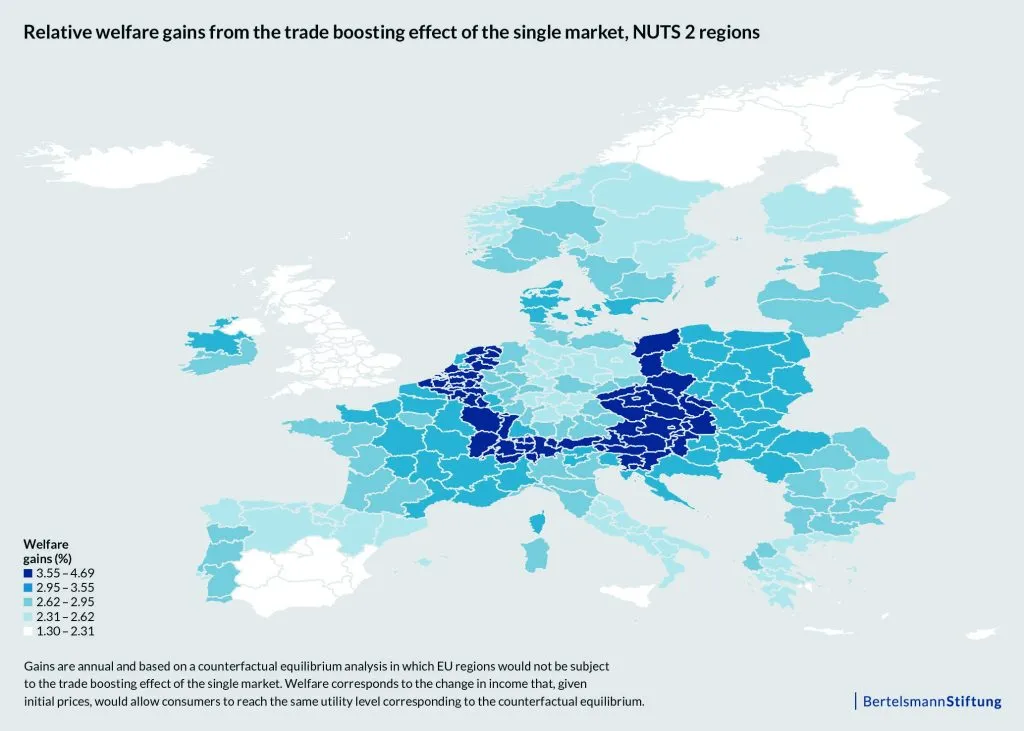

Our 2019 study calculated the economic benefits of the EU single market for member states and countries with strong economic ties to the EU. The study compared two scenarios: the existence or the absence of the single market—a hypothetical look at a world with or without the EU single market.

The study found “the single market provides higher welfare, higher productivity and lower markups to all its members while at the same time countries outside the single market are actually (slightly) worse off because of the existence of the common market.” Free-trade access to the single market yields great economic benefits to members, and the weight of the EU single market actually drags down the economic activity of countries outside it.

Of all the countries evaluated, Switzerland was one of the biggest winners, due in no small part to its access to consumers and labor in neighbors Germany, France, and Italy (the EU’s three largest economies, now that the UK is out).

According to the study, Switzerland experiences a yearly welfare gain of 4.02% measured in income amounting to €2,914 per capita (highest in the results), a yearly gain in productivity of 3.4% (third in the results), and a decrease of 3.57% to product markups (third again). Austria, which has a similar population at 9 million to Switzerland’s 8.6 million, sees around half the income gains (€1,583 per capita).

Beyond the numbers, what Switzerland losing access to the single market would look like is not hard to imagine. One needs only to look across the English Channel to see the same case playing out.

Comparing Switzerland to the UK

January 31, 2022 marked the end of a transitional period for checks and controls on goods imported from the EU into Britain. The UK’s Revenue and Customs agency predicts a four-fold increase in customs declarations, which they estimate will significantly burden EU-UK trade in the coming year. The UK is already feeling the effects of Brexit, with a recent estimate (October 2021) of monthly losses from trade amounting to 15.7%.

Although this milestone has long been on the horizon, it has been hard for small and medium-sized businesses to prepare for the new rules and to reach customers in EU markets. Businesses and consumers alike in the UK and the EU will feel the sudden impacts of higher customs duties and longer transit times. British exporters may have to seek other markets outside the EU to recoup sales, and EU consumers may think twice about ordering UK goods when they see longer delivery times and high import duties.

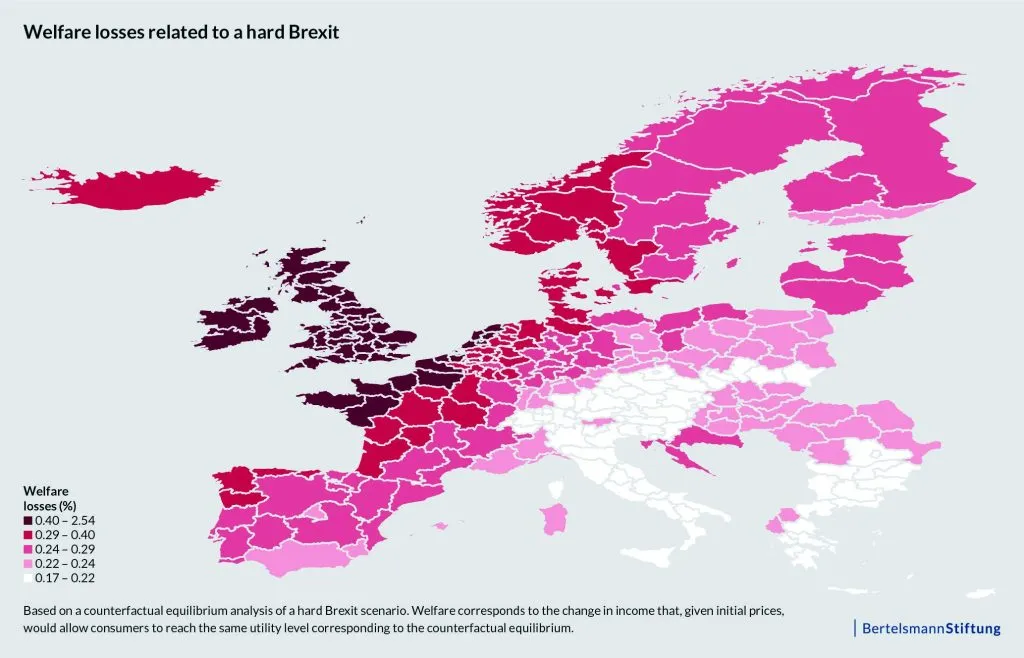

This will have a big impact on the UK and EU economies. Another 2019 study, Estimating the impact of Brexit on European countries and regions, built upon the calculations of the economic benefits of the single market by adding a third scenario: What happens when the single market exists, but the UK is now on the outside looking in?

A hard Brexit, the paper estimated, would result in a €873 per capita income drop (-2.39%) and an overall cost of more than €57 billion for the UK. If the single market simply didn’t exist at all, that overall cost would be just €50 billion, so a hard Brexit results in losses even greater than the gains the UK saw from being in the single market.

This is extremely relevant for the Swiss case, since the benefits of access to the single market for Switzerland are even larger than those of the UK and more evenly spread when compared across its regions. In the UK, for example, per capita income gains range from over €3,000 in inner London, to just around €250 to €500 in the islands and northern regions.

In Switzerland, all regions see income gains of around €2,500 to €3,500 for being part of the single market. Those numbers qualify Switzerland as one of the countries with the highest relative and absolute welfare gains thanks to access to the EU single market.

How will this affect the EU?

When it comes to the EU, regions closest to the UK that had high volumes of trade were predicted to be hit hardest by Brexit in relative terms, according to the 2019 study. Some of the biggest losses in relative welfare were seen in Ireland, Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, France, and Norway.

From this, it follows that EU countries closest to Switzerland would see similarly high relative welfare losses, namely Switzerland’s top three EU trading partners: Germany, France, and Italy. Together, these accounted for 35% of Switzerland’s exports and 26% of its imports in 2019.

It is neither in the economic interest of Switzerland nor of the EU’s three largest economies to let the free trade deal lapse, but political conditions in Switzerland present a challenge. Any deal will need to face a referendum in Switzerland, and recent polls suggest it will be a difficult task.

A 2018 poll revealed that 48% of those asked were against the institutional framework, and just 43% were for it. However, a full rejection of the EU was not apparent—another poll of Swiss public opinion in 2021 found that 54% of respondents thought the bilateral agreements between the EU and Switzerland were advantageous. Further, a referendum to reject Schengen rules entirely, called by the Eurosceptic Swiss People’s Party in 2021 (the largest party in the Swiss National Council), was rejected 62% to 38%.

What happens next?

Given the high economic stakes, it is hard to believe the EU and Switzerland would let the free trade agreements expire, but the same was said about Brexit. Both Brussels and Bern are dug in and it will be hard to shift out of their corners.

Switzerland’s emphasis on direct democracy with regular referenda will make it difficult for the free trade agreement to pass the domestic political test while including the EU’s desire for full freedom of movement and the ECJ’s role in dispute settlement.

Meanwhile, the EU is not ready to make concessions and feels that it has already been patient and lenient with Switzerland, pointing to Switzerland’s contributions to the cohesion policy. Switzerland has not contributed funds to the cohesion policy since 2012, despite an agreement that it would do so since 2008.

The EU hopes Bern presents a clear plan and roadmap to signal a willingness for constructive negotiations.

What will the UK do?

Given the economic benefits trade with the EU carries, what happens with Switzerland will be of interest to the United Kingdom, whether Switzerland deepens its ties with the EU or lets the trade agreements lapse.

With new UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak seeking ways to restart the UK economy amidst reports that it is expected to shrink the most in 2023 amongst G20 nations bar Russia, it makes sense to hear murmurings of a “Swiss Model” in London. Access to the EU single market increased welfare in Switzerland and the UK, as shown in the pair of 2019 studies referenced in this article, and the UK is looking for a way to kick its economy back into gear.

However, Sunak is adamant that his government will not pursue such a course, saying, “On trade, let me be unequivocal about this. Under my leadership the United Kingdom will not pursue any relationship with Europe that relies on alignment with EU laws.” Such a model contains many red lines that Brexiteers would not cross, and thus such a path could existentially threaten Sunak’s government. Whether this idea comes back around in the future, and how the Swiss-EU relationship evolves, remains to be seen.

For now, it seems rumors of the UK government considering a “Swiss Model” were little more than a quick temperature check for closer EU-UK trade relations. The temperature appears to remain extremely cold.